This post is the third and final post in a series entitled, “Perceptions.” Previous posts have explored themes of skepticism and mistrust, on the part of Jamaican people, surrounding some of Jamaica’s recent business engagements with China. This post explores whether similar perceptions are held throughout the Caribbean at large as China expands its sphere of influence in the region.

This post is the third and final post in a series entitled, “Perceptions.” Previous posts have explored themes of skepticism and mistrust, on the part of Jamaican people, surrounding some of Jamaica’s recent business engagements with China. This post explores whether similar perceptions are held throughout the Caribbean at large as China expands its sphere of influence in the region.

For many of Jamaicans, the increasingly visible presence of Chinese workers, expats and government officials’ throughout the country harps to memories of a colonial legacy of exploit and unilateral benefit by an external power. We hypothesize that this fear of neo-colonization has cultivated doubt that Chinese infrastructure investments will benefit Jamaicans in the long run. Further, having explored the conversations generated in Jamaican media, we recognize that these public perceptions are being validated by the lack of agency accorded to Jamaicans by the government to actively participate in the direction of the country’s development. Thus, our discussions have affirmed that we [Jamaicans] do perceive as strange, the unfamiliar. What remains to be explored, however, is the response of other Caribbean nationals to their own countries’ strengthening of ties with China and whether patterns of apprehension and mistrust are similar throughout the region.

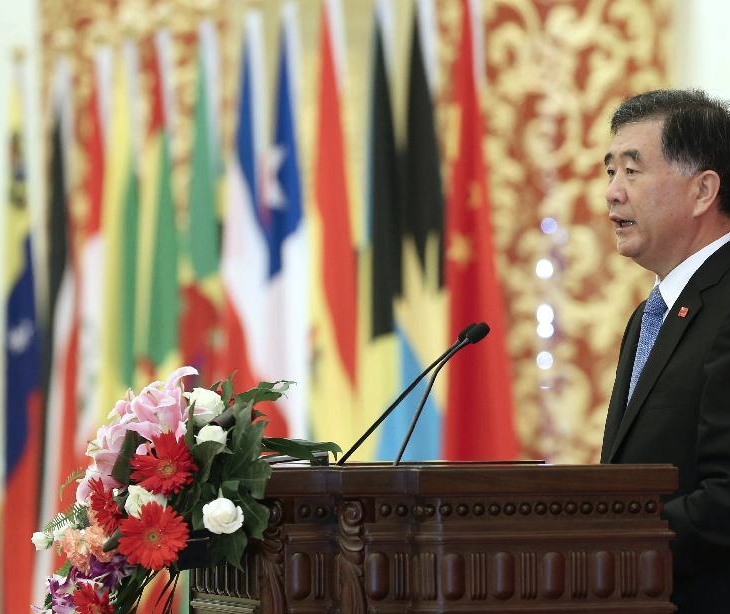

It is no secret that China has been strategic in their bid to increase their sphere of influence in the Caribbean. China’s 2008 Policy Paper on Latin America and the Caribbean was the country’s first explicit attempt to make this strategy known. In light of this, China is committed to establishing itself as an investor in large-scale infrastructure projects in the Caribbean.

Most recently, for example, Trinidad and Tobago’s Government signed an agreement with China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC) to develop an economic zone and a transshipment port along with dry-docking facilities. This agreement juxtaposes China’s expressed interest for a $1B investment in Jamaica’s proposed Logistics Hub, earmarked specifically for the offshore Goat Islands. Both Jamaica’s and Trinidad and Tobago’s port development proposals are being propelled by the anticipation of an expanded Panama Canal in 2015. As in Jamaica, it appears as though public skepticism towards China’s business arrangements are shared in Trinidad too.

What happens in one Caribbean country may (or may not) have implications for how other countries view their long-term well-being, particularly when it comes to their respective engagements with China. Therefore, it is difficult to ascertain as yet whether a general sentiment of mistrust is shared among Caribbean nations though this is quite possible. Given that coverage of Jamaica’s ongoing relationship with China does appear in news outlets of other Caribbean nations, one can’t help but wonder, will Caribbean countries look to the Jamaica-China relationship as a foreshadowing of where their own business relationships with China can lead?

Ultimately, it is evident that national interests articulate louder than a collective regional concern for a host of reasons. China has been clear in its intentions to primarily engage with countries that support its One China Policy and this cannot be said for the Caribbean nations that have more favorable relations with Taiwan. As each island leverages its own economic strategy, it will be interesting to see whether regional public interest in the China-Caribbean or China-Jamaica relationship will garner traction.

About The Author: Zaneta Scott

More posts by Zaneta Scott